CONCORD, N.H. — Researchers who spent three years dragging sheets of fabric through the woods to snag ticks have created a detailed map they claim could improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease.

The map, which pinpoints areas of the eastern United States where people have the highest risk of contracting Lyme disease, is part of a study published in the February issue of the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Though the areas highlighted as high-risk likely won’t surprise anyone familiar with the disease, the research also showed where the disease likely is spreading, and it turned up some surprising information about the rate at which ticks are infected with the bacteria that causes it, researchers said.

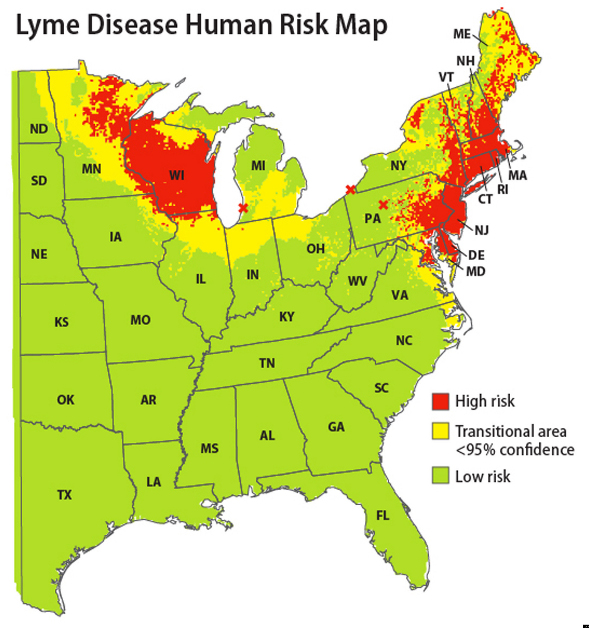

The map shows a clear risk of Lyme disease across much of the Northeast, from Maine to northern Virginia. Researchers also identified a distinct high-risk region in the upper Midwest, including most of Wisconsin, northern Minnesota and a sliver of northern Illinois. Areas highlighted as “emerging risk” regions include the Illinois-Indiana border, the New York-Vermont border, southwestern Michigan and eastern North Dakota.

“The key value is identifying areas where the risk for Lyme disease is the highest, so that should alert the public and the clinicians and the public health agencies in terms of taking more precautions and potential interventions,” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Maria Diuk-Wasser of the Yale School of Public Health. “In areas that are low risk, a case of Lyme disease is not impossible but it’s highly unlikely, so the clinician should be considering other diagnoses.”

Named after a small Connecticut town, Lyme disease is transmitted by the bite of tiny deer ticks. Antibiotics easily cure most people of Lyme, but other than the disease’s hallmark round, red rash, early symptoms are vague and flu-like. People who aren’t treated can develop arthritis, meningitis and some other serious illnesses.

Previous risk maps were heavily reliant on reports of human infections, but those can be misleading because the disease is both over- and under-diagnosed, according to the study. Where someone is diagnosed is not necessarily where the disease was contracted, and ticks may live in a region long before they actually infect someone, meaning there could be a significant risk even without confirmed cases.

The study was published this week based on data collected between 2004 and 2007. Diuk-Wasser said the high risk areas likely haven’t changed, but there might be some changes in the transitional areas. The map is still useful, however, because it highlights areas where tick surveillance should be increased and because it can serve as a baseline for future research, she said. And it provides new information about the infection rate among ticks, she said.

About 1 in 5 ticks collected were infected – more than researchers expected – and that percentage was fairly constant across geographic areas, she said. Researchers had expected the infection rate to vary.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention counted more than 30,000 confirmed or probable cases of Lyme in 2010, the latest data available. More than 90 percent of those cases were in 12 states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Wisconsin

Dr. Jodie Dionne-Odom, New Hampshire’s state epidemiologist, said the map may be a useful tool for states where Lyme disease is just emerging. But for New Hampshire, it doesn’t provide any new information because the state does its own detailed tick monitoring.